In Love With My New OLD Typewriter

/I’ve fallen in love with my new OLD typewriter. And the memories it evokes.

This typewriter belonged to the previous owner’s grandmother. I bought it with memories of my mom.

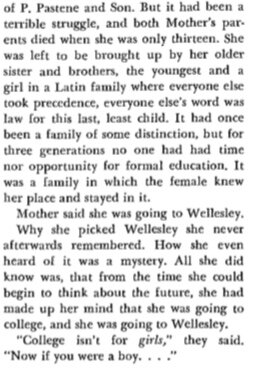

I grew up hearing the rapid tap-tap-tap of my mom's fingers hitting the keys of her most reliable friend, her black typewriter. It resided on a movable grey metal table in an area of the living room close to the kitchen and within earshot of whatever door we used to enter the house. Though movable, that typewriter stayed put, and my mom always seemed to be typing on it – letters to friends, notes for her academic papers, and lots of letters to all of her kids, as they left home. I first got mine during my senior year of high school when her typed words arrived on light blue airmail stationary since she sent them from Oxford, England to Rome, Italy. By the next year, I eagerly awaited her letters as I stood near the mailboxes in my dorm at Wellesley College waiting for the postman to sort the mail, and there was always lots of it. Then, her letters reached me at my tall apartment building on the East Side of Manhattan, and then, when I became a correspondent for Time magazine, they would be in the outdoor mailbox that I’d stop at on my way from my car to my second floor apartment in Los Angeles. Finally, and to a diminishing degree, her letters flew in through the mail slot of the front door of my three-decker home in Cambridge.

But by then she’d started to use a computer, so while her letters kept coming they didn’t carry with them the lingering smell of ink on paper, and the words seemed flatter on the page due to the absence of her typewriter. For a time my mom kept her typewriter next to her computer, turning to use it when special occasions calledto her to use it.

Back when I was almost a teenager and the nation grieved after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, my mom went to her typewriter in our Amherst, MA home. There, unbeknownst to me, on November 25, 1963, she typed her letter of condolence to her Hyannis Port neighbor and childhood “swimming rival,” Robert F. Kennedy, whom she addressed as “Bob.”

Later when my mom encouraged me to learn how to type, she told me that when I mastered the keys by touch alone, no looking, I would think through my fingers, racing to keep up with my thoughts. She was right, but as years later I read her letter of sympathy to her childhood acquaintance, I grasped that she was doing much more through her fingers –she as feeling. In her letter to “Bob,” my mom shared her own searing, unbearable pain of her loss of her beloved sister, Betty, as she found words to try to comfort him. Even at an early age I knew my mom had experienced in the sudden tragic loss of her sister a burden of grieving that would “never become bearable” for her – “only less unbearable, over time.” I knew this even if I never heard her say those same words to me.

Several years after my mother’s death, my childhood friend, Ellen Fitzpatrick, who grew up with me in Amherst, MA, sent me this letter. She’d discovered in when researching her splendid book, “Letters to Jackie: Condolences from a Grieving Nation.”

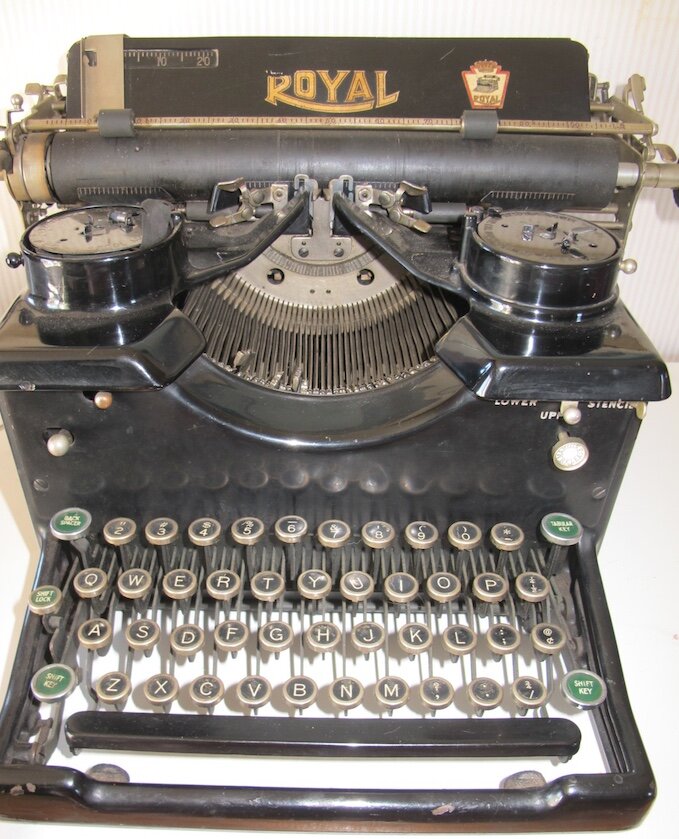

When my desire to own an old black typewriter hit hard, I sent word to my sister, Betty, who frequently wanders through estate sales and returns home with gems. Last Thursday she called to say she’d found this one in an online marketplace. On Saturday morning, I drove about 40 minutes and bought it from a woman whose grandmother had owned it. Her granddaughter described her as a woman who never worked and who she always remembers as wearing white gloves. It's a mystery, Diane told me, why she had this typewriter, though as she later recalled her grandfather worked at The Boston Globe, so perhaps he’d brought a used one home from the office for her to use. By the time Diane and I shared these stories by text and email and then in person, talking about our moms and grandmothers, she assumed me that she knew her grandmother would want me to have it.

I own it now, giving it a new home in my living room.

Soon I will order a new ribbon so again I will hear the tap-tap-tap of fingers, still ones not nearly as fast as my mom's were, pushing down on these keys on my new OLD 1930's Royal typewriter. It will be fun to watch its thin, metal arms rise to meet the paper I roll into this heavy machine, and watch as letters rise off the page, carrying with them that smell of ink.

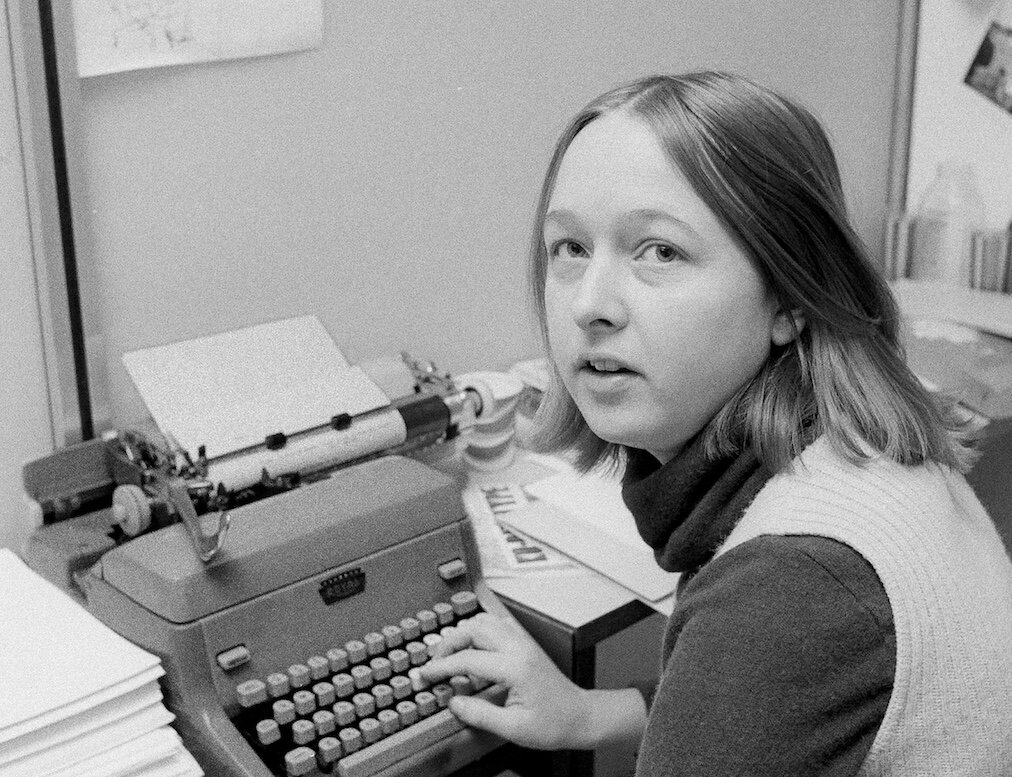

It was on 1970s version Royal typewriters that I began my journalism career at Sports Illustrated. When I was shown my office at the magazine, a few items were there – a metal desk and swivel chair, a dial telephone, mostly used to call the Time Inc. operator so they could place long distance calls when I was fact checking stories, and a blue metal typewriter on its own stand.

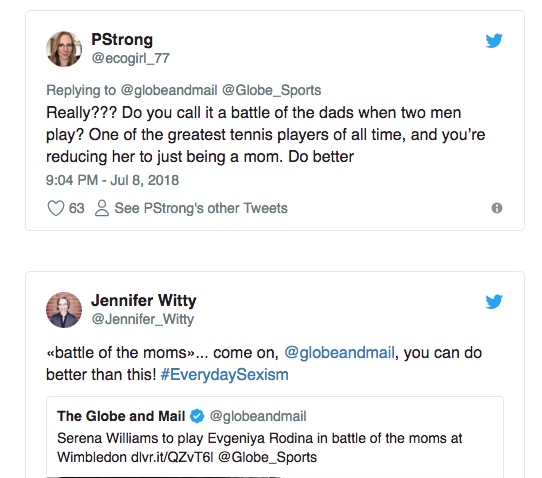

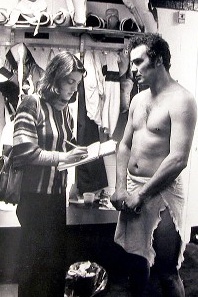

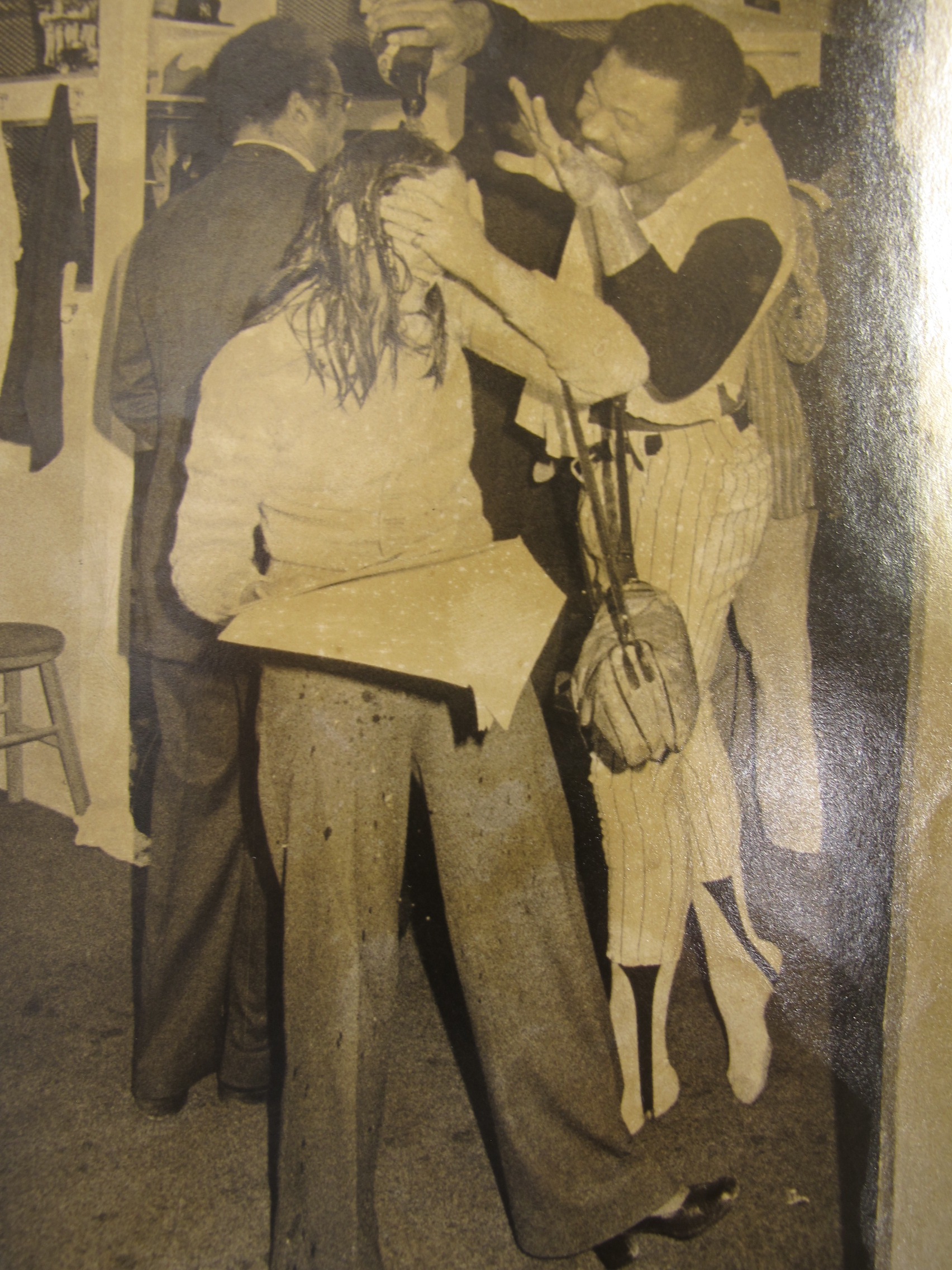

On my office typewriter, in an uninterrupted burst of words, I typed my October memo documenting the events of October 11, 1977, when Commissioner Bowie Kuhn banned me from entering any baseball locker room to conduct interviews there, as the rest of the reporters did, all of whom were male. My editor, Peter Carry, asked me to write a memo to document what transpired that night at Yankee Stadium, which he told me he’d send to Commissioner Kuhn. This became a contemporaneous record of what happened to me that night, and thus served as evidence in our federal legal case, Ludtke v. Kuhn.

My office at Sports Illustrated. Photo by the Associated Press.

I shared my memo with a few friends at Sports Illustrated, one who returned it with these words in red, referring to me by my office nickname. At that time, I often wore Western shifts I’d bought in Austin, Texas when I’d visit my brother, Mark, who attending the University of Texas in Austin.

![My Sports Illustrated co-workers at our annual [Walter] "Bingham Bowl." We worked and played sports together, but when it came to the paychecks we received for the jobs we did I'm pretty sure the women, including me, were paid less than the guys. An…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a5782bf8c56a8ca76a395df/1517843164233-W5Q6IPYS94IZ51UABCBK/Sports+Illustrated+Staff+Photo+1974.jpg)