A Team for the Ages: We Hope!

/By Lisa Laskin, Season Ticket Holder, PWHL Boston Team’s inaugural season

From her second row seat at Boston’s first professional women’s hockey game, Laskin, a fellow rower, described what she saw and felt.

Boston wore their home green uniforms

Overall, great experience. High value: Excellent hockey, good venue, and league is working hard to deliver an exciting experience, and it isn't expensive. The crowd was enthusiastic and knowledgeable: the roar that greeted the first Boston goal was extremely satisfying. The announcing of the team was kind of a roll call of great hockey players, culminating with the captain, Hilary Knight, who got a huge cheer.

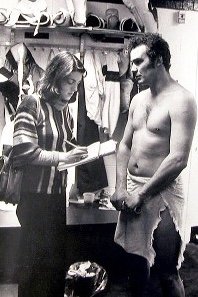

Hilary Knight, photo by Tanner Pearson, Boston Glob e

As for the game, Boston came out tentative, a little slow, and Minnesota took advantage. Minnesota was fast and confident seemingly putting pucks on net from the get-go. They figured out immediately how to shoot high on the Boston goalie, Aerin Frankel. Boston picked it up in the second period, and then really brought their game in the third, which was super exciting. That they ended up losing despite having outshot Minnesota almost two to one is testament to Minnesota goalie Nicole Hensley's skill. It is not for nothing that she is a multi-medalist at both the Olympics and IIHF Women’s Worlds, so good. Frankel for Boston is no slouch but my expert commentator companion suggested that she might have gotten a little rattled mentally when Minnesota’s very first shot went right by her into the net and it is hard to get your head back after that.

The PWHL game is fast and more physical than college hockey. The women can't check on open ice but more body contact generally is allowed and they are taking advantage of it. Fans who are used to a certain way of calling the games took some time to figure it out. Someone would get hit or go sprawling, and all the arms of the hockey parents in the seats would go up with sputtering cries for a penalty. But they played on. There was a lot of satisfying crashing into the boards, exciting if you are right down on the glass like we were. The final few minutes were frenzied in front of Minnesota’s net. I read that they put four shots on net in the last minute, or something like that. But as The Boston Globe wrote, Hensley caught the final shot as the buzzer sounded and raised her glove high over her head. That kind of said it all.

Afterwards, the teams had a handshake line (as you do in hockey) and then skated around for hugs and then joined for a great group photo.

Great game, see ya next Monday for Ottawa.

Boston Team came together at the net before the game

You could tell the players were just thrilled to be there doing that hockey. I really like how the PWHL is working to get the word out about the league and teams to local media - lots of good news coverage, and even The Hockey Writers daily Substack newsletter is listing the scores and they NEVER ever talk about women's hockey. Also nice how hard the league worked at this game to show how this team fits into the local hockey community - from the Cap (Bergy) and his kids doing the ceremonial puck drop, through small Wizards on the ice for the anthem, a lively intermission game from Chelmsford-Billerica girls, and interviews with college players in attendance who'll be in the Beanpot and played with some of the now pros. It feels like this team is being welcomed into the local hockeytariat. Donny Sweeney from the Bruins was there, and lots of kids in attendance, wearing Boston Pride gear or their own hockey clubs. Boston jerseys seemed to be doing a brisk business. I got a special PWHL hat for being an inaugural season ticket holder.

I'm told by another knowledgeable source – my brother, former CNN and MSNBC tech director and hockey fan – that the NESN commentary on the YouTube channel was pretty good (high praise from him), although another source told me it wasn't as good as the CBC/TSN for the Canadian games. The YouTube channel will show the local network broadcast of every game, for free, which is great. Again, good on ya PWHL.

Only downside: home games played in Lowell. I mean, it's a GREAT rink. But it is in Lowell which is a bit of a poke to get to on a Wednesday night. And trying to get into the parking lot before the game was, as my friend put it, a goat rodeo (whatever that means). Honestly, if they were in Boston or closer to the city, they could pull from the South Shore and would definitely fill an arena.