As a Generation Fades from View, Its Stories Will Endure

/By Melissa Ludtke

I knew my friend Robin was battling ovarian cancer.

I just never thought she’d die.

Of course, I knew her odds of beating this disease weren’t good, but I was unwilling to accept that one day I’d wake up to hear that the first of our groundbreaking crew of women sportswriters from the 1970s was gone. I didn’t want to face this gaping hole.

Last week I clicked on a personal note in Facebook messenger:

“I heard Robin Herman died. If true, a very sad day. You and she were the pioneers.”

Resisting, still, I Googled three words I never wanted to write together: “Robin Herman obituary.”

The Boston Globe confirmed my fear.

Alone, in the stillness of that young morning, I wept.

Then, my phone rang, while social media spread word of Robin’s passing far, wide, and fast.

When I saw Jane Leavy’s name appear my cell phone, I knew the news of Robin’s death had found her.

Melissa Ludtke, Jane Leavy, Robin Herman at Fenway Park, 2018. Photo by Paul Horvitz.

A baseball writer for The Washington Post in the late 1970s, she’s the best-selling author of biographies of Mickey Mantle, Sandy Koufax, and The Big Fella, her most recent one about Babe Ruth. On a chilly night, late in 2018, Jane had come to Fenway Park to talk about The Big Fella, and Robin had come to hear her, with her husband, Paul, and so did I. We sat at adjoining tables as Jane spoke, then after she signed books, the three of us carved out space to be together for what would be our first and last time.

On the phone, Jane spoke of the specialness of our evening together, and I knew why. To see and hear us that night, gregarious and loud, was to intuit that we’d long been close chums. Appreciating that our time was short, and with much to say, we talked over each other sharing stories for which any of us could supply the ending. We’d bonded intimately, tightly, and unshakably with the glue of emotional fortitude shaped by all of the experiences we’d had separately decades earlier but were imprinted on us. Back then, we were on our own in doing our jobs, steeling ourselves for the possibility of being bullied or hit on, ignored or humiliated, as men tested our mettle. We’d persevered in spite of the barriers – blocking our access to locker rooms while male writers interviewed players – that these same men put up, which made it really tough for us to do our jobs.

Make it hard on us, they thought, maybe we’d go away.

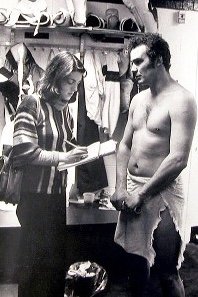

Robin Herman kept out of the Chicago Blackhawks’ locker room

None of us did.

Soon, Lesley Visser called me with Robin on her mind. I was struck by how each of us had reached out to connect as we did before text and social media came between us. We just wanted to talk, tell stories, and laugh together to ease our collective pain.

Lesley was the first woman The Boston Globe hired to write sports a few years after The New York Times hired Robin to be its first woman sportswriter. That morning, Lesley had said of Robin in the Globe: “When you’re the first, you know you’re doing it for everybody, and boy, she was the perfect role model. … [she was] iron under velvet. She was lovely, and yet she was not going to be abused.”

Then, I called Lawrie Mifflin, who’d been the first woman hired to write sports by New York’s Daily News, a few years after Robin. Assigned to pro hockey, as Robin was, Lawrie recalled Robin welcoming her, making her feel at home by selflessly sharing all she knew about this team, all the time knowing she and Lawrie would tell New Yorkers about the Rangers ‘ games for competing newspapers.

Robin. Jane. Lesley. Lawrie. And me, the first national woman baseball beat reporter when I worked for Sports Illustrated.

Despite gaps in time and the distance of our separations, we knew to whom to turn that morning. For what each of us endured, what we accomplished together, fills an important chapter in American’s ongoing fight for equal rights. For us, too, Robin’s death signals a reminder of how our generation is departing, and not too long in the future the threads of our collective memory will be untangled, thus rendering parts of this history threadbare.

It's why we tell our stories now.

Robin Herman working in hockey Locker room

Robin fed her blog, “Girl in the Locker Room … and other women’s tales from back then,” so generations after hers would appreciate why she had to “muster Supreme Court-worthy arguments for an inane essentially logistical problem [denial of locker room access] that could easily have been solved by a few big towels.”

Robin Herman’s Blog @ http://girlinthelockerroom.blogspot.com/

Lesley wrote Sometimes You have to Cross When It Says Don’t Walk: A Memoir of Breaking Barriers to leave a trail behind of her extraordinary path-carving NFL broadcast career.

Lawrie stayed in daily journalism for three decades, serving as deputy sports editor at The New York Times along the way, a mentor to so many.

When Jane writes baseball, she does it with the gift of prose steeped in the game’s history with her woman’s touch, as she writes about in her essay, The Phallic Fallacy.

“When I became a sportswriter in 1977, the unstated goal was to write lean, mean, macho prose. We couldn’t make ourselves invisible in the locker room, so we tried to make ourselves invisible in our writing. How many times did I dare my friends to remove the byline from my stories and try to find any place where my words sounded as if they were written by a girl? We weren’t supposed to acknowledge the differences gender might produce, much less flaunt them. But the truth is, women in the locker room do see things differently–and I don’t mean anatomically. We come to sports with different assumptions and experiences. We are outsiders, which is what reporters are supposed to be. The femininity we sought to hide is actually our greatest asset, our X-ray vision.”

It’s why I spent years figuring out how to write my book about Ludtke v. Kuhn as a compelling story for younger generations.

Because men dominated the media in the 1970s, they hijacked the telling of our stories about our push for equal access and fair treatment. In those versions, our quest for fairness was transformed into a tale of pesky, immoral young woman wanting to enter locker rooms to leer at naked ballplayers, pretty much ignoring all issues of justice through equal rights.

Robin reclaimed her story later on, leaving us a lasting legacy of her persistence and courage in challenging the men’s rules and practices that made it tough to do that job she loved.

Her story, our stories, are ones I believe younger generations want to hear.

Melissa Ludtke, the plaintiff in Ludtke v. Kuhn, the 1978 federal case that opened equal access for women sportswriters. At the time, she was a baseball reporter for Sports Illustrated, and is writing a book about her legal case.